by Salim Mansur

“To God belong the Names Most Beautiful.”

— The Qur’an (7:180)

“God is beautiful and He loves beauty.”

— Muhammad, the prophet of Islam.

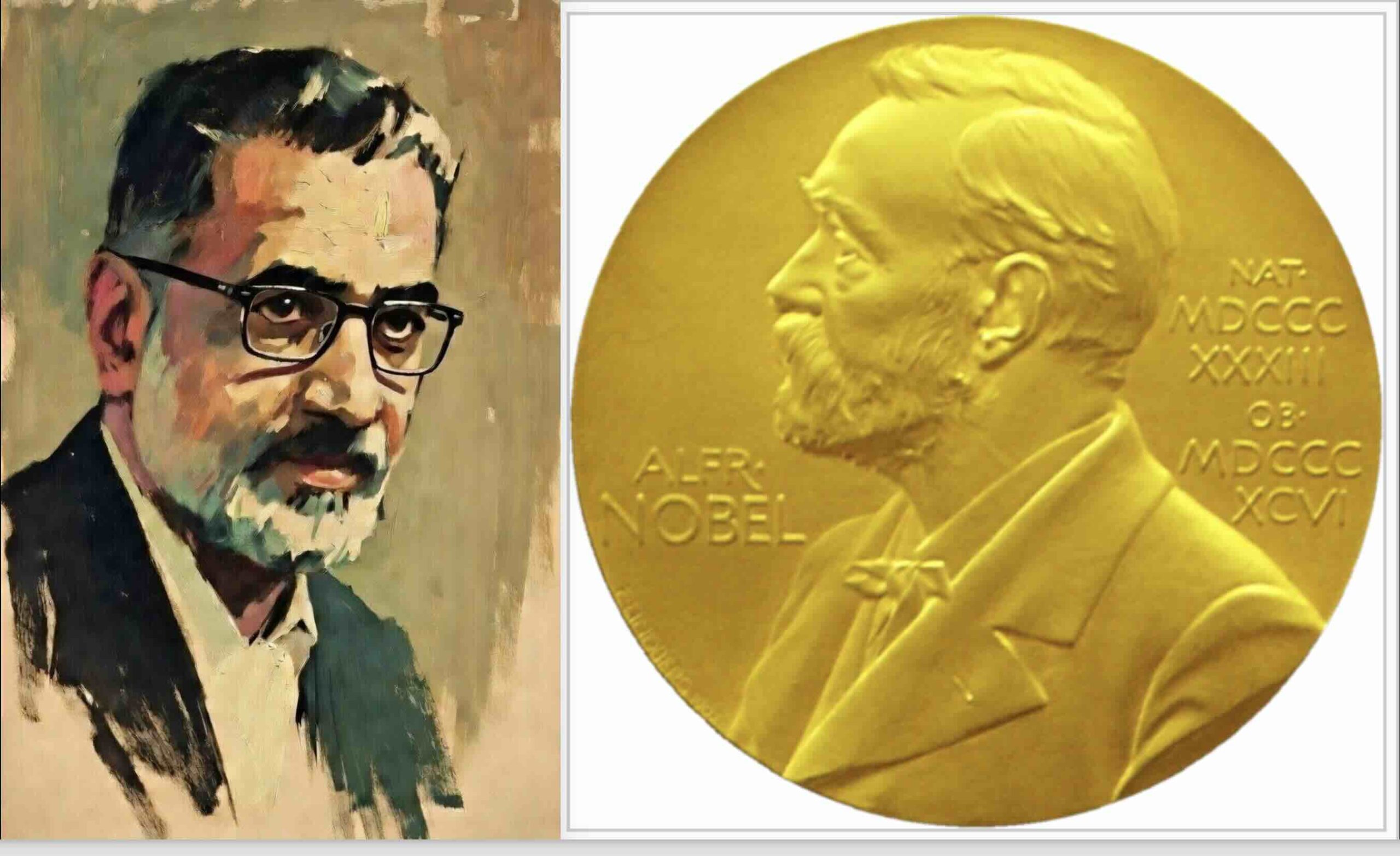

[Note: I wrote this tribute in honor of Professor Abdus Salam on his passing in November 1996 and was published in the London (UK) based Sufi journal in the Spring 1997 issue. I am re-publishing it in memoriam of Professor Salam’s centenary year of his birth in January 1926 in British India. Professor Salam was the first Muslim physicist/scientist awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1979, which he shared with Steven Weinberg and Sheldon Glashow “for their contributions to the theory of the unified weak and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles, including, inter alia, the prediction of the weak neutral current.” One of the finer biographies of Professor Salam is by Gordon Fraser, Cosmic Anger: Abdus Salam – the Muslim Nobel scientist, published by Oxford University Press, 2008. In his Introduction to Salam’s biography, Fraser writes, “Science underpins the whole of our world and governs our lifestyle, but – remote and difficult in its mathematical form – has become a neglected branch of culture. Scientists who change our view of the cosmos are overshadowed by celebrities who superficially appear to contribute more to the tides that affect the affairs of men. Abdus Salam was no such Cinderella scientist.”]

The 1979 Nobel Prize for Physics was awarded jointly to Professors Abdus Salam, Steven Weinberg and Sheldon Glashow. Their work showed that of the four fundamental forces of nature, namely, gravitation, electromagnetism, weak and strong interactions within atoms, electromagnetism and the weak force might be seen as one. Salam named the unification of these two forces of nature as ‘electroweak’. Ever since the work of Einstein, physicists have searched for ways to show the grand unification of all the forces of nature, that they emanate from one primary source. The work of Salam, Weinberg and Glashow was a step in the direction of working out the grand unification theory.

For Salam the Nobel Prize was just one more station in a long journey begun when he left his home in 1946 as a young man of twenty. He headed for St. John’s College, Cambridge, to study under Professor P.A.M. Dirac. Dirac was an eminent physicist, who shared the 1933 Nobel Prize for Physics with Erwin Schrodinger for welding together Einstein’s Special Relativity with the Quantum Mechanics of Heisenberg and Schrodinger. It was quite fitting that when Salam received his Nobel Prize, Dirac was the referee. The Nobel Prize remains the highest recognition awarded to an individual for achievement of a stellar nature in sciences, literature and the promotion of international peace. Salam is the only Muslim scientist accorded the honor by the Nobel committee and, as he stated at the Nobel banquet, the award to him confirmed the stipulation of Alfred Nobel that neither race nor color should stand in the way of acknowledging the achievement of an individual.[1] The passing away of Salam on November 21, 1996 in Oxford, England at the age of seventy brought to a close the life of one of the most distinguished men of the twentieth century. It was a life that will stand as a beacon of hope, achievement and excellence for innumerable young students of developing countries wanting to study basic science for bringing prosperity to their society, and for those Muslims who may venture beyond the rituals of their faith to understand the deep mysteries of the universe as part of their religious obligation.

Salam was born in Jhang, a small unremarkable town in Punjab on the banks of the Chenab. Punjab was then a united province in a united India, relatively prosperous from its agriculture fed by the tributaries of the Indus. It is said that the future physicist’s father had a dream in which he learnt of a son to be born in his family who would achieve great honor. Salam’s father, Choudhary Mohammed Hussain, was a teacher in the local government school. The family had a modest income. He named the boy born to his second wife, Hajira Begum, Abdus Salam, meaning a servant of peace. The boy would exceed in achievement and honor everything his father could have imagined.

Abdus Salam showed very early in life a special gift of learning. He stood first in the entire province of Punjab when he passed his Matriculation examination. Subsequently, he again secured the first position in the Intermediate examination and left to study in Government College, Lahore. Here he took special interest early on in pure mathematics, working with Ramanujan’s equations. His first published paper written in 1942, when only sixteen, was to show solutions to some of Ramanujan’s problems. He also played chess and took deep interest in Urdu poetry. His love for poetry reflected his attraction to the mystical knowledge of Islam cultivated by Sufis, the simple living folks whose love for Allah transcended the boundaries of rituals and sectarian loyalties. His father forbade him to play chess, and he found that the pure mathematics of Ramanujan was not as appealing as the lure of physics with its search for answers to real problems posed by nature. His father encouraged him to write the Indian Civil Service (ICS) exam that would gain him a place in the elite administrative service of British India. But Salam demurred. In 1945 he took his Masters. Then fate would intervene even as the politics of undivided India hurtled to its destiny with sectarian violence, religious animosity and the tragedies accompanying the partition of the subcontinent.

In 1946 the united government of Punjab under Chief Minister Khizar Hayat Khan found in the treasury an unused amount of money for the British war effort. The chief minister was persuaded by some of his officials to make that money available as scholarship for promising students to study abroad. It was a fortune that smiled at the right moment for Salam. He secured admission to Cambridge and the money was provided for Salam to proceed to England. Here he came upon some work given to him by a senior research student dealing with problems of quantum electrodynamics, then a new field. Salam solved the problem given to him, and in the process made an important contribution to ‘renormalizing’ (eliminating infinities from) meson theories. This would be his doctoral thesis. Thus, in Cambridge, Salam acquired his reputation as a gifted physicist. He was offered a position in the Institute of Advanced Studies at Princeton. But due to bureaucratic regulations he could not submit his work as a thesis for doctorate in Cambridge until 1952. His extended scholarship expired in 1951 and Salam was required to return to his home, now a new country called Pakistan.

Salam’s experience at Government College, Lahore, was an unhappy one. There was little appreciation of his special talents as he was driven to teach and perform administrative chores that were intellectually unrewarding and emotionally brutalizing. Some of his administrative superiors resented him. The political situation in Pakistan also deteriorated at this time over sectarian issues. The Ahmadiyya sect, a neo-Muslim group to which Salam belonged, was targeted by ultra-orthodox and conservative Muslim organizations led by Maulana Maududi of the Jamaat-i-Islami. They demanded that the Ahmadiyyas be declared non-Muslims for what was seen as their heretical belief in regarding the founder of their group, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, as a Messiah or prophet. This ran counter to the fundamental belief of Muslims in general that Muhammad was the last Prophet of God, and that with him and revelations to him, which form the Koran, prophethood and divine prophecy came to an end. The anti-Ahmadiyya agitation showed the ugliness of sectarianism when politics was joined to religion to inflame public opinion.

In January 1954 Salam returned to Cambridge with his wife and daughter. This marked the beginning of his life as an exile from home. The poverty of his experience as a scientist in Lahore, a city once respected for its support to learning, came to symbolize the problem of developing societies of Asia, Africa and Latin America where the inadequacy of resources and absence of support by governments to the advancement of scientific learning offered little hope for breaking the cycle of poverty and dependency. This experience would propel Salam to devote as much energy to further the cause of investment for the advancement of basic science by developing countries as to solving the riddles of nature. It became one of the major themes of his life’s crusade.

The other theme, to rekindle among Muslims the love and devotion for knowledge and science in keeping with the teachings of the Koran and the Prophet of Islam, was directly in response to the bigotry of the ultra-conservative Muslims whose views had slowly suffocated what was once an enlightened Islamic civilization. The sectarian troubles in Punjab drove Salam away from home, but he did not sever his links with Pakistan. In subsequent years, especially during the period of the Ayub era in the sixties, Salam frequently travelled to his country as a scientific advisor to the government. But twenty years after he left Lahore, Ali Bhutto as President of Pakistan reduced by half in 1971, declared the Ahmadiyyas to be non-Muslims. This exposed the Ahmadiyyas without any protection to the ridicule, intolerance and violence of a society easily driven to excesses by the bigotry and sectarianism of ultra-conservative Muslim politicians. Salam sadly responded with a quote from Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in the West) who was also declared an infidel by Muslim dogmatists of his era: “If you accuse me of being a Kafir [infidel] this is not a simple matter. There is no faith stronger than my faith [in Islam]. I am unique in the world, and even this unique person you call a Kafir. If you call this unique person a Kafir, then there is no Muslim left in the whole world.”

Even before the Nobel recognition Salam had gained a worldwide reputation for his passionate advocacy of investment in basic science in developing countries. His personal experience in Pakistan on returning from Cambridge in 1951 illuminated the problem of science and scientists in developing societies. Salam did not have the personal funds, given the salary of an academic in a third world country, to provide for himself scientific journals, the single most valuable source for keeping informed of the latest developments in science and for communicating with others. The nearest fellow scientist with whom Salam could communicate while in Lahore was located in Bombay. And when Salam travelled at a short notice to meet Wolfgang Pauli, a Nobel Laureate and celebrated physicist visiting Bombay, he was reprimanded by his superiors on his return. There was inadequate facility for research, the library was poorly stocked, and there was practically no one around in Lahore with whom Salam could exchange ideas. The isolation of a scientist in a developing country meant that either the scientist would have to flee to the West or abandon science. Many years later in a lecture at the University of Ottawa, in September 1982, Salam recalled his dilemma. “In that extreme isolation in Lahore, where no physics literature ever penetrated, with no international contacts whatsoever and with no other physicists around in the whole country, I was a total misfit… I must either leave physics research or my country. With anguish in my heart, I made myself an exile in 1954. Before I left I swore I would bend my energies to making it certain that others like me are not faced with this cruel choice, of either remaining in science or in their countries.

Though Salam was compelled to leave Pakistan in 1954, his experience in Lahore taught him that there was an urgent need to stop the ‘brain drain’ from developing to developed countries. The solution he came upon was to establish a center for the study of basic science where scientists from developing countries could converge on their own time and ‘recharge’ their intellectual batteries. Such a center would provide a clearing house of ideas, a place for training young scientists from developing countries, a retreat for those needing a break from teaching, a place for research and, where the eminent and the budding scientists could meet informally to share their work with one another. More than anything else Salam felt that the pride of his labors was the establishment in 1964 of the International Center for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) at Trieste, Italy. The idea for such a center was promoted through the United Nations and the International Atomic Energy Agency, and with the critical support of the Italian government Salam’s vision for a center was realized. John Ziman, on the occasion of presenting Salam with the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Science by the University of Bristol in July 1981, noted: “A single line in his [Salam’s] biodata records that he has been Director of the International Center for Theoretical Physics at Trieste since 1964. There is more in that title than the fifty awards he has won from universities and national academies around the world. He created that Center out of nothing: it is now one of the most successful and respected international institutions of our times.”

For Salam the sustaining drive to establish the ICTP and propagate the idea of investment in basic science in developing countries came from his ever deepening faith in Islam. Salam tried to educate politicians and policy makers in the third world that relying on the import of modern technology as a means for the development of their societies was insufficient and myopic. He pointed out that technology was a by-product of basic science, and unless the developing countries began to invest in basic science, of which physics was a leading edge, their reliance on imported technology meant deepening a dependency relationship with the advanced industrial societies. It further meant that only those technologies would be made available for importing which became obsolete in the advanced countries, and while doing nothing to cease ‘brain drain’ there would be insufficient manpower training available to create a pool of trained workers to handle such technologies. He repeatedly pointed out wherever he went that it was science and the vision of scientists which made the modern world. Typical of his sage counsel was the lecture he presented in Edinburgh in 1989 on being honored with the first Edinburgh Medal. Here he said,

Both the industrialized and the developing countries spend 5.6% of their respective GNPs on defence. The educational expenditures are also similar—5.1% for the industrialized versus 3.7% for the developing countries. For health it is 4.8% for the industrialized versus 1.4% for the developing countries—admittedly, a difference, but not as striking as for Science and Technology. The figures for Science and Technology differ from each other by nearly an order of magnitude… The industrialized countries spend 2-2.5% of their GNPs on Research, Development and Modification, Adaptation plus the Utilization of Science and Technology versus less than 0.3% (on UNESCO’s estimates) for most developing countries.

Salam repeatedly emphasized that this difference in investment in science between developed and developing countries was not simply a gap, it was a chasm becoming ever wider and the possibility of bridging this becoming ever remote.

The theme of the widening chasm between the North and the South, the developed and developing countries, preoccupied Salam. It showed his commitment to theoretical physics was joined to a wider responsibility as a man dedicated to world peace, to building bridges among cultures, to the upliftment of the human condition among four-fifths of the human race. There was a time when North and South, East and West, were roughly at parity, or even when the South and the East were ahead of the North and the West in the level of civilization attained. But the situation had dramatically changed, and the unbridgeable gulf in the standard of living between the developed and developing societies threatened ominously the future of the planet. In a lecture at the University of Stockholm in September 1975, Salam drew attention to this theme in the following manner:

To get behind the psychological thinking of the poorer humanity, you must understand how recent in our view this disparity—which makes untermenschen of us today—is. It is good to recall that three centuries ago, around the year 1660, two of the greatest monuments of modern history were erected, one in the West and one in the East; St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and the Taj Mahal in Agra. Between them, the two symbolize, perhaps better than words can describe, the comparative level of architectural technology, the comparative level of craftsmanship and the comparative level of affluence and sophistication the two cultures had attained at that epoch of history.

But about the same time there was also created—and this time only in the West—a third monument, a monument still greater in its eventual import for humanity. This was Newton’s Principia, published in 1687. Newton’s work had no counterpart in the India of the Mughals. I would like to describe the fate of the technology which built the Taj Mahal when it came into contact with the culture and technology symbolized by the Principia of Newton.

The first impact came in 1757. Some one hundred years after the building of the Taj Mahal, the superior firepower of Clive’s small arms had inflicted a humiliating defeat on the descendants of Shah Jahan. A hundred years later still—in 1857—the last of the Mughals had been forced to relinquish the Crown of Delhi to Queen Victoria. With him there passed away not only an empire, but also a whole tradition in art, technology, culture and learning. By 1857, English had supplanted Persian as the language of Indian state and learning. Shakespeare and Milton had replaced the love lyrics of Hafiz and Omar Khayyam in school curricula, the medical canons of Avicenna had been forgotten and the art of muslin making in Dacca had been destroyed making way for the cotton prints of Lancashire.

As a scientist Salam believed, and this is where he held out hope for the developing societies, that through proper investment in education with emphasis on the teaching of basic science the unknown promise of future discoveries could be harnessed for the war against poverty. He often recalled for Muslim audiences the words of the Prophet of Islam that “‘poverty may become synonymous with kufr’… There may be other criteria of kufr [unbelief] as well, but in the conditions of the twentieth century, in my opinion the most relevant criterion of kufr is the passive toleration of poverty without the national will to eradicate it.”

Salam was, however, unable to convince a majority of the leaders of the developing countries, and more particularly Muslim countries, to seriously advance the cause of development by investing in basic science. The appeal of importing technology as a quick-fix to the challenges of development and economic growth overrode the arguments of Salam. The political leaders refused to see for any number of reasons that nurturing scientists, what the developed countries take for granted, is intimately connected with wealth production and prosperity. For Salam this obtuseness on the part of the third world leaders was brought home to him in a most personal manner when he visited Pakistan on invitation of the military leader, General Zia-ul Haq, following the Nobel award. Salam felt that the prestige of the occasion offered him an opportunity to suggest something practical. At the state banquet in his honor Salam suggested he would place his entire share of the Nobel prize money, about US $66,000, towards a scholarship fund for Pakistani students pursuing higher studies in science abroad provided the government contributed one million US dollars in establishing such a fund. The President, General Zia-ul Haq, agreed on principle but left it to the Governor of Punjab to examine Salam’s proposal and make a public announcement the next day. The announcement came, to Salam’s utter dismay, that the Government of Pakistan would match his contribution dollar for dollar. Salam responded that if this was all that the government could offer, he would then establish the fund all by himself. He did.

In a world that had become skeptical about religion, Salam was a scientist driven by an abiding faith in the vision of Islam. He did not view his religion as an obstacle to his science. On the contrary, he felt his understanding of nature grew in depth as he ventured more deeply into the meaning of his faith in Islam and in his reading of the Koran. The following verse from the Koran he cited most often in his public lectures:

Thou seest not, in the creation of the All-Merciful any imperfection. Return thy gaze, seest thou any flaw. Then return thy gaze, again and again. Thy gaze comes back to thee dazzled, aweary (67: 3-4).

“This, in effect, is the faith of all physicists, the faith which fires and sustains us; the deeper we seek, the more is our wonder excited, the more is the dazzlement for our gaze,” Salam had said many times.

It was not ironical that Salam was moved by the notion of symmetries. In this he was reassured by the Koran, that in Allah’s creation no imperfection could be detected, that all of creation was in balance and in symmetry.

In his address to the Annual All Pakistan Science Conference in 1961 held in Dacca (spelt now as Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh), Salam remarked, “I would have liked to show you that with all his pragmatism, the modern physicist possesses at once the attributes of a mystic as well as the sensitivity of an artist.” That there is symmetry in nature, and hence beauty, has been variously expressed. Keats summation of this idea is most well known.

Beauty is truth, truth beauty—that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, an astrophysicist at the University of Chicago, a south Indian born in Lahore, a Cambridge man and a Nobel Laureate in Physics like Salam, was also deeply moved by the idea of aesthetics in science. He believed that the creative energy of scientists, like that of the artists, poets and musicians, was in part moved by the sense of beauty in nature and the quest to express that beauty in as pleasing an aesthetic manner as nature rightfully deserved. Chandrasekhar cited Heisenberg’s definition of beauty as “the proper conformity of the parts to one another and to the whole”; and Kepler’s, “Mathematics is the archetype of the beautiful.” And Poincare who wrote, “The Scientists does not study nature because it is useful to do so. He studies it because he takes pleasure in it; and he takes pleasure in it because it is beautiful. If nature were not beautiful, it would not be worth knowing and life would not be worth living… I mean the intimate beauty which comes from the harmonious order of its parts and which a pure intelligence can grasp.” For Salam the ultimate confirmation of truth and beauty in nature as Allah’s creation was provided by the eloquence of the Koran.

As a Muslim, Salam insisted that far from there being any contradiction between the teachings of Islam, the Koran as divine revelation to Prophet Muhammad, and science, the reverse was true. He pointed out frequently, as he did in his speech at the Nobel banquet and in the Nobel lecture, that Islam was the inspiration for Muslims to engage in scientific activities. The Islamic culture and civilization at its most glorious hour during the early middle ages was a boon for science and the pursuit of knowledge in all fields. Citing the work of the Harvard historian of science, George Sarton, as the authoritative source on this subject, Salam would point out that the age of science between 750 A.D. and 1100 A.D. was a period of unbroken succession of Muslim names as dominant figures of science and philosophy. Jabir, Khwarazmi, Razi, Masudi, Wafa, Biruni, Avicenna, Ibn al-Haitham, Omar Khayyam, were Arabs, Turks, Afghans, Persians in origin, but they all belonged to the Commonwealth of Islam. For the next two and a half centuries Muslim names would still be prominent in the world of science, but alongside would emerge for the first time, since the passing of the Greeks, European Christian names like Roger Bacon. Slowly the Muslim world would be eclipsed, fall behind, and then eventually lose its political independence to the powers of Europe.

Why did science decline in the Muslim world with such devastating consequences after such noble achievements? This is a puzzling question, with no answer completely satisfactory. Salam speculated, suggesting internal causes of dogmatism and religious intolerance being more responsible for the reversal than external causes of military defeats brought about by the Mongol invasion. He appealed to the Muslim world to recreate the spirit of the earlier Islamic culture and civilization, to foster a new Commonwealth of Muslim countries which would once again focus their collective energy and resources to the improvement of their people through cultivation of knowledge.

Andalusia, or Spain, during the period of Arab-Muslim rule symbolized the essential spirit of Islam as accommodation and tolerance for the nurturing of science, philosophy and arts. Salam often drew attention to this spirit. In a lecture to the “International Religious Liberty Congress” meeting in Rome in September 1984, Salam dwelled on the teachings of Islam for fostering religious liberty and tolerance. He said, “As a Muslim, liberty of religious belief and practice is dear to me since tolerance is a vital part of my Islamic faith. As a physicist, it is important to me in that religious liberty practiced in any society guarantees also liberty of scientific discussion within it and a tolerance of rival views, so crucial to the growth of science.” In Andalusia, this liberty of religious belief and tolerance nurtured the coexistence of Muslims, Christians and Jews, secured a culture that rewarded the pursuit of science and philosophy, and in turn the society prospered. In the same lecture he pointed out the repeated reminders in the Koran with respect to religious liberty and tolerance. The Koran declares:

There shall be no compulsion in religion. (2:256)

Proclaim O Prophet, This is the truth from your Lord; Then, let him who will, believe, and let him who will, disbelieve. (18:29)

We have not appointed thee a keeper over them. Nor art thou their guardian. And revile not those deities whom the unbelievers call upon and worship. (6:108-109)

Salam explained,

This tolerant injunction in respect of even those which Islam believed were false deities, turns to an injunction of positive reverence so far as the leaders of other revealed faiths are concerned, with the enunciated principle: “There has been a guide sent to every people.” And the clear injunction: “We differentiate not among anyone of the Lord’s messengers [to mankind].”

To summarize then, the Holy Book, in the clearest possible terms, makes religious liberty a fundamental part of a Muslim’s faith. It states that the role of the prophet is to convey Allah’s message, he has no authority to compel anyone nor has he a responsibility regarding the acceptance of the faith he preaches. And finally, at the very least, an attitude of respect is due to leaders of all Faiths.

The problems of the world, war, hunger, diseases, ignorance, poverty, all of these and more reflect the flaw within man, not with God or nature. For Salam the scientist and Salam the man of faith, the perfection in nature and the excellence of Islam were essential truths, independent of man. Salam often quoted the Koranic verse, “Allah changeth not the condition of a people until they [first] change that which is in their hearts.” The ever worsening social and economic conditions of Muslims, despite the teachings of Islam and the example of the Prophet, showed the excellence of Islam as an autonomous truth independent of the history of Muslims as a people, that when they had absorbed the lesson of their faith they excelled as a community of believers. Similarly, the excellence of science stood apart in the normative sense from the practice of man.

Men of science could formulate means to overcome the problems of the world, just as they could with their weapons of destruction lay the world to ruin. Salam spoke of the time when he heard Linus Pauling, recipient of two Nobel prizes, give a lecture at the Nobel symposium in 1969 in which he described the need to levy a tax on the rich of the world for raising the living condition of the poor. Salam noted, “Pauling spoke of the transfer of resources of the order of 200 billion dollars per year, about 8% of the world’s then total income, which he thought was the right figure for an international tax. I remember listening to Pauling and thinking to myself, this is a totally utopian proposal. None took it very seriously at the meeting.” But then Salam knew in his heart, as his own life testified, that vision and action would have to be brought together, however utopian such vision may initially appear, if the ever widening chasm between the two unequal halves of mankind, the rich and poor, was going to be reversed.

As a man of faith, Salam held out the hope that man as God’s special creation, endowed with intelligence, out of self-interest and the deep abiding consciousness of the transcendent within him will eventually fulfil his obligation to his fellow man. As a man of science, Salam worked his entire adult life both to unravel the mysteries of nature and to make available the tools of his vocation to improve the human condition. It is rare when in one individual, faith in the transcendent and the pursuit of scientific knowledge, come together in a perfect combination. Such an occurrence is a gift of heaven. The dream of Salam’s father was a premonition. Professor Abdus Salam was one special gift from above.

References:

Salam, M.A. 1994. Renaissance of Sciences in Islamic Countries. Edited by H.R. Dalfi and M.H.A. Hasan. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co.

——. 1989. Science in the Third World. The First Edinburgh Medal Address. Edinburgh University Press.

——. 1984. Ideals and Realities. Selected Essays of Abdus Salam. Edited by Z. Hassan and C.H. Lai. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co.

Singh, J. 1992. Abdus Salam: A Biography. New Delhi: Viking Penguin Books.

Chandrasekhar, S. 1987. Truth and Beauty. Aesthetics and Motivations in Science.The University of Chicago Press.

Note

[1] Since Professor Abdus Salam was awarded in 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics, there have been four other Muslim scientists awarded Nobel Prize in Chemistry: (i) Ahmed Zewail, 1999, Egypt; (ii) Aziz Sancar, 2015, Turkey; (iii) Moungi Bawendi, 2023, Tunisia; and (iv) Omar M. Yaghi, 2025, Jordan (origin, Palestinian refugee family).